Quality: People Before Process

J.L. Griffiths, FCMC CTDP

Quality is the key to success. Creating quality – that is, delivering what’s promised to the customer (and then some) the first time, every time should be the aim of every organization. But what drives quality? Is it the process? Technology? People? Something else?

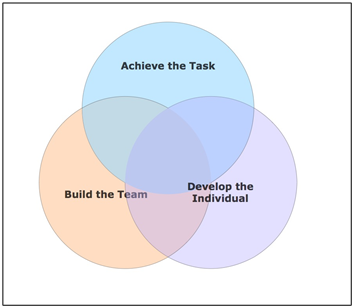

I believe that quality occurs at the intersection of human competency and effective process – what Subir Chowdhury has called “people power” and “process power”[1]. Process power is tangible, and generally, something that is understood (or at least “figure-out-able”) – most management systems are designed to ensure that processes are robust, consistent, and reliable. But even the best processes are useless without the individual and collective competency of the people who are charged with executing those processes to deliver what the customer demands.

People Over Process Isn’t A New Idea

This idea of people being the key isn’t exactly new – Peter Drucker described “Knowledge Workers” (which these days is pretty much everyone), and the need to change organizational paradigms to make the most of these valuable resources, back in the 1960s [2].

Knowledge workers come to the party with highly refined individual technical skills. Organizing those skills effectively to generate the most value for the organization and its customers is the challenge. Simply putting a bunch of talented people in the same room and throwing a project at them is clearly not sufficient (see BELLOW).

| From CMMI to P-CMM: Human Capital Drives Process Execution Success At the beginning of my consulting career in the early 2000s, I worked on a project with the systems engineering department of a North American aerospace and defence contractor. At the time, they were all-in on Carnegie Mellon’s “Capability Maturity Model Integration” (CMMI)[1] approach to process excellence, eventually achieving a Level 5 certification (the highest), indicating that they had terrific processes. Despite this, they still struggled to deliver the quality and on-time performance that their customers demanded. We weren’t alone in this; in fact, many engineering organizations in the early 2000s had similar experiences. This prompted the development of the “People Capability Maturity Model” (P-CMM) in the late ’90s to address the human side of quality performance. P-CMM is a helpful, albeit never widely adopted addition, but it still focuses primarily on systems and processes, which ignores the essential aspect of quality performance: organizing people with the right blend of competencies so that they can collectively develop (and execute) processes to generate excellence in the eyes of the customer. |

Individual skills are important, but they are rarely enough – to use a sports analogy, it isn’t the team with the best players that wins a championship, but rather it’s the players on the best team. How do you get there?

Drop the Puck and Get Out of the Way: Quality Results Through Distributed Leadership

Sticking with the sports analogies: as a Canadian, I find it helpful to think of the world of work as though it were a hockey game (that’s ice hockey, in case you’re wondering).

At its highest level, hockey is a beautiful, exhilarating game of speed and movement and improvisation. You can’t micro-manage a hockey game: there are just too many variables, not the least of which are six players wearing a different coloured jersey doing their best to stop you from succeeding. In this dynamic environment, it’s up to the players – individually and collectively – to react situationally in order to be successful. Drop the puck – and get out of the way! Who’s in charge? Whoever has the puck – and that’s a variable that’s constantly shifting and changing as the game goes on. Chaotic. And yet, somehow, it works.

The role of coaches and managers at this level is to identify the total skill set – that is, the competencies – of their players and create small teams within the team (forward lines and defensive pairings), and insert these groupings into a high-level system and game plan that will best counter their competition in any given situation. The thing to remember is that it isn’t the system that wins, rather, success is determined by the players’ ability to effectively use their competencies and those of their teammates in the context of a general plan that they adjust dynamically and autonomously in real-time within the chaotic pace of the game. It’s the decentralized control and distributed decision-making and leadership – which is only possible with a clear understanding of competency – that determines success: the quality outcome that the customers demand.

Quality in Your World

Chances are you aren’t running a hockey team – but the same principles apply. In today’s rapidly changing competitive landscape, the team that can best adapt and still deliver the quality that customers demand will be successful. Getting there requires good processes, but success is ultimately dependent on people.

Unfortunately, the “machine paradigm” that informs the way many companies are organized (cogs in a wheel, people neatly arranged in org charts) doesn’t adapt well to change. Leaders who want quality must have highly skilled, engaged, motivated people, organized effectively, who will not only execute processes well, but who will overcome weaker processes and succeed anyway. In fact, those people will naturally and constantly look for ways to improve whatever processes exist.

Running this type of organization takes a different kind of leadership that embraces the challenges of a rapidly changing and increasingly complex reality. It isn’t easy – but it is possible. I’d like to illustrate this with an example from my own experience.

The Little Squadron that Could

My first career was as an aerospace defence officer in the Canadian air force, and one of my career highlights was the four years in the early nineties that I served in a mobile tactical radar squadron. During that time, there was a massive effort to prevent illegal drugs from entering the US and Canada, which involved a host of law enforcement agencies (federal, state/provincial, and local) as well as the military from both countries. As part of that effort, the US military deployed a number of air defence radar units to help detect and track aircraft attempting to smuggle drugs from South and Central America.

In August of 1992, Hurricane Andrew ripped through the Caribbean, Florida and the Gulf Coast, killing 65 people and causing over $US27 billion in damage. In addition to the thousands of homes and businesses that were damaged or destroyed, this powerful Category 5 storm also wreaked havoc on those aforementioned surveillance radars deployed for the counter-narcotics mission.

As part of NORAD – the joint air defence treaty between the US and Canada – my little Canadian radar squadron was scrambled to fill a gap that Andrew created in the US radar coverage.

So 12 of us packed up (literally) all of our squadron’s equipment onto a single US C-141 Starlifter transport plane, and we took off into the night to be dropped off in the middle of nowhere, where we spent the next couple of months providing covert 24/7 radar surveillance to the US Customs narcotics interdiction efforts. It was a tough job, but we did well.

We ran that operation with just the 12 of us – and never more than 3 of us at the operations site at a time – for weeks. When we were given notice that we were to deploy back to Canada I was amazed to find out that the US unit that was going to replace us was bringing 75 people to do the same job.

How were we able to do so much, for so long, with so few?

The answer – like the hypothetical hockey team I described above – lies in a combination of individual and collective competency, and distributed leadership.

Although we all had specialties, everyone on our unit was cross-trained, and able to do at least part of the job of the other specialties. That meant extra help where and when needed – like the forwards “back-checking” to help the defence, or the defence “joining the rush” in a hockey game. In addition to the broad and deep skill set, the entire unit was completely bought into what we had to do, fully engaged, and proud of being “small but mighty” – it became our badge of honour.

How did we get there? First, we were brutally clear about our strengths, and our weaknesses, individually and collectively, and there was no shame (or blame) in talking about them. We regularly had open discussions throughout the unit on where we could improve, and how we could better leverage the skills that we had, and those conversations were led not just by officers, but by everyone.

Because we didn’t have the luxury of enough of anything, we learned, and then actively embraced, an approach to distributed, situation-oriented leadership; literally, whoever “had the puck” – that is, the person with the visibility into the problem and the ability to fix it – was in charge, and had full authority to harness the rest of us to get things done. Once that particular problem was solved, the “puck was passed”, and this dynamic approach allowed us to do things that shouldn’t have been possible with such meagre resources (remember, we were replaced with a unit over 5 times as large).

We didn’t get there overnight, or by chance. The key was a conscious effort over a couple of years to fully understand ALL of the skills of the people on our team – not just the ones associated with whatever their occupational specialty or position in the org chart, but all of the skills they possessed, regardless of how or where they were acquired. Acknowledging and tapping into “whole-person competency” gave us a level of capability and flexibility that belied our size.

For example; one member of our team was a Heating/Ventilation/Air Conditioning (HVAC) technician who was assigned to us to maintain the heat exchangers for the radar. As it turned out – because we took the time to learn – he was a pretty outstanding general mechanic and wound up looking after all of our generators and small engines as well, and ultimately he learned to be a reasonably skilled radar technician on top of that. In another case, one of our operations specialists was an amateur carpenter – and we used their skills to direct the rest of us in building – and then improving – a hut cobbled together from scrounged and salvaged material to get the crew out of the sun. Once we got that built, our HVAC tech jury-rigged a crude air conditioning system so we had some respite from the heat. And it wasn’t just that deployment – those sorts of things happened all the time.

Another example; we had a problem of equipment overheating. The radar maintenance folks were stumped, and it looked like we might have to abort the mission. Then a clerk – probably the least technical person on the unit – made a brilliant suggestion. Our modular tents were Canadian standard, double-walled, with an inner liner made of white nylon parachute-like material to provide better insulation in cold Canadian weather. Why not set up a few sections of modular tent inside-out over the radar van so the sun would reflect off the white fabric? That simple fix, suggested by a non-technical team member as part of the open problem solving and improvement dialogue that had become our norm, saved the mission.

An Elite Unit? Maybe…

We certainly considered ourselves an ‘elite’ unit, and by any established metrics we were. And yet… there was no special selection process, no one was hand-picked for service in the squadron, people were posted in and out just as they would have been to any other unit in the air force. We had the same processes, manuals, technical orders and operational plans as everyone else. What enabled the quality that made us so different was a conscious approach to a different kind of leadership.

By listening, respecting, and valuing all of the skills of everyone, regardless of their role or official place in the hierarchy, and then working constantly and collaboratively to improve skills both within and outside our specialties, we built up trust in each other, and in our collective ability to tackle whatever challenge was put in front of us. This allowed us to practice a kind of “distributed” leadership that guaranteed quality performance in ways that processes couldn’t begin to address.

We got comfortable with not having the answers but knowing we could figure it out. No spare parts? No problem – we’ll cannibalize other less important bits of the system to jury-rig a repair that isn’t in the manual. No supplies? We’ll make what we need ourselves until the supply system catches up. We did it all the time. And we did it all without spending an extra dime.

Quality – delivering what was needed, when it was needed, to serve our mission – was the inevitable by-product of a focus on the people side of our ‘business’.

Process is important. But it’s people that generate quality, with everything they do individually and collectively. If you want your quality metrics to improve, focus first on the human side of the operation. The results – and the ROI – will astound you.

About the Author

A leading practitioner in the optimization of the interface between individual competency and organizational design, Jeff Griffiths is a principal at WorkForce Strategies International, a Canadian-based workforce and organizational development consultancy that helps clients achieve extraordinary results by focusing on the competencies – both overt and hidden – within their business.

Jeff is a Fellow Certified Management Consultant (Institute of Certified Management Consultants of Alberta) and a Certified Training and Development Professional (Institute for Performance and Learning).

In addition to his role at WorkForce Strategies, he is a Senior Fellow at the Canada West Foundation, a member of the Workforce Council at the North American Strategy for Competitiveness (NASCO), and a member of the National Learning Network for the US Chamber of Commerce Foundation’s Talent Pipeline Management initiative.

Jeff can be reached at jeff@workforcestrat.com

[1] Chowdhury, S. The Ice Cream Maker. New York, Doubleday Currency. 2005

[2] Drucker, Peter F. The Effective Executive. New York, Harper and Row. 1967

Previous: Competency Frameworks – How Much Detail is Enough?

Next: Scoping a Competency Project

Read With Us

If you found this information useful, please subscribe to be notified for our next great post.